A Traveler's Tribute to Trees

The Cypress Tree Tunnel at Point Reyes, California, is worth a stop, especially for photographers.

Story and photos by Rebecca Holland

Rebecca is a freelance travel and food writer based in Chicago. You can find her on Instagram.

The drive from Olympic National Park to San Francisco features spectacular views of towering forests.

Eighty miles from Seattle, in the northwest tip of the continental United States, lie nearly 1 million acres of wilderness. Olympic National Park and the surrounding Olympic National Forest are known for their diversity, encompassing glacier-capped mountains, rugged coastline and old-growth temperate rainforests.

Driving along the Pacific Coast of the forest, I saw sea stacks, sandy beaches and islands in the distance. What I found most spectacular, though, were the trees. The conifers in Olympic National Park are more than 20 stories tall. They’re joined by cathedral forests of Douglas firs and Sitka spruce, western red cedar and big-leaf maples. What’s so amazing about these trees is not only their massive size, but the different ways in which the park and forest services protect their diversity.

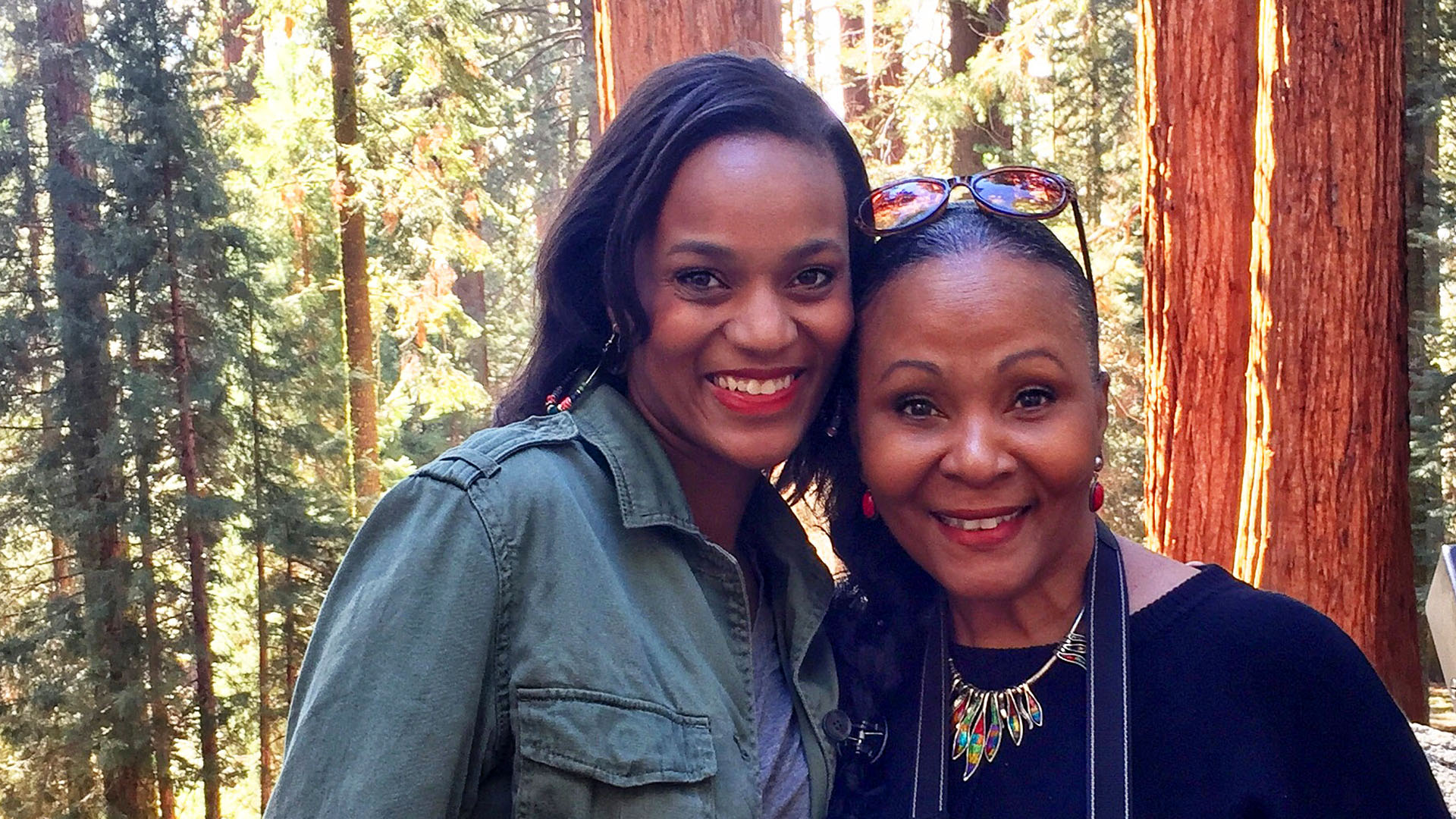

Armstrong Redwoods State Natural Reserve

A deer wanders in Olympic National Park.

In the 1860s, there was a battle of sorts between Gifford Pinchot and John Muir about how federal land should be managed. John Muir was for preservation, which is essentially no human intervention, while Pinchot was for conservation, which is protection of land while also using it responsibly. Eventually, with the help of President Theodore Roosevelt, Pinchot’s vision came through in the form of the National Forest Service — which now includes more than 193 million acres of land. Muir’s vision also came to life as the National Park Service, which encompasses more than 100 million acres of land. Because of this arrangement, national parks are surrounded by national forests, and the two are managed differently but work together.

Logging, some mining, and other uses of land for government profit are allowed in national forests but not in national parks, as long as the uses do not negatively impact the ecosystem. In national forests, selective logging and thinning can help areas to have healthier trees, more diversity and less intense fires. Cleaner air, a higher reproductive rate of trees, and habitat creation are all benefits of healthy trees.

Both approaches create stunning beauty that is best viewed firsthand. Several trails allow you to take advantage of the diversity of trees in Olympic National Park. I walked through the Valley of the Giants on the Quinault Rain Forest Nature Loop, a half-mile trail that connects to several longer trails. The Hall of Mosses Trail, a 0.8-mile loop, or the 1.2-mile Spruce Nature Trail are within the park's Hoh Rain Forest. Both walks are filled with giant, mossy trees that made me feel like I was in another world or on the set of a fantasy movie.

Olympic National Park features beautiful hikes through trees. Photo by David Sandel

The Cascades Lake Scenic Byway features 19 stops, including the Sparks Lake Trail.

Trees and Trails in Oregon

After being humbled by the forest in Washington, I began the drive to Oregon for more astounding views. For a quick route (a little under three hours), take Interstate Highway 5 to the Columbia River Gorge. If you have more time, scenic U.S. Highway 12 (a little under five hours), goes through Gifford Pinchot National Forest, named after the Forest Service’s first chief. The Columbia River Gorge canyon cuts through the Cascade mountains, and the drive provides views of cliffs to the north in Washington, and smaller mountains and waterfalls to the south in Oregon. Along the way, there are numerous wineries you can visit that specialize in grapes such as albarino and zinfandel. You also can buy fruit from the Hood River farmers market and check out the cute local boutiques along the way.

As I continued to drive south through Mount Hood National Forest, I saw Mount Hood in the distance. Like Olympic, this forest is filled with old growth. I moved on, through Willamette National Forest and Deschutes National Forest, where the Forest Service was conducting controlled burns.

I camped in Deschutes National Forest for the night, then drove the 20 miles to Bend, Oregon, for a day outside of the trees. Lone Pine Coffee Roasters was the perfect place to refuel. Bend is known as one of the best hiking cities in America, and every customer at Lone Pine was decked out in gear. Some had kayaks and other outdoor equipment strapped to their cars. I was told Rimrock Trail was a nice, short day hike, and I wasn’t led astray. The 1-mile trail along the Deschutes River was beautiful and not too strenuous.

Afterward, I rewarded myself with hard cider and doughnuts at Avid Cider Company and pizza from Pizza Mondo. Down the street, I learned about Oregon’s famous pinot noir at Naked Winery, which has a great tasting room and selection of local wine. If you’re more of a beer drinker, try Deschutes Brewery or BBC brewery, known for craft beer and a great outdoor patio and grassy area beside the lake. For dinner, try Lebanese cuisine at Joolz, paella at Barrio, award-winning sushi at 5 Fusion & Sushi Bar or American comfort food at Pine Tavern.

The drive to Armstrong Redwoods State Nature Reserve passes through wine country.

Crater Lake is the deepest lake in the United States.

California’s National Forests

On the way out of Bend the next morning, I took the Cascade Lakes Scenic Byway, a 66-mile road with viewpoints and outdoor activities along the route. I stopped for the Sparks Lake Hike, a 19.5-mile trail with openings for views of a glistening lake and stratovolcanoes — large, steep-sided, symmetrical cones built of alternating layers of lava and ash.

When my time on the byway ended, I continued south toward Crater Lake National Park. Created by the collapsed Mount Mazama volcano, the lake is 1,949-feet deep, the deepest in the United States. Its depth absorbs the sun’s longer red rays and reflects the shorter blue and violet rays, creating a vibrant color that is unlike anything I’ve ever seen.

After an hour or so of gazing at the view, I continued south out of Crater Lake National Park, passing mountain hemlock, Jeffrey pines, sugar pines and other trees that survive well in Oregon’s cold winters. From here into northern California, I hit national forest after national forest. I passed through Klamath National Forest and Six Rivers National Forest before stopping for the night in Shasta-Trinity National Forest, the largest national forest in California.

Further to the west, Redwood National and State Parks are home to the largest trees in the world. But if you don’t have time for the westward detour, you can see similar trees at Armstrong Redwoods State Natural Reserve, just south of Mendocino National Forest. In this grove, check out the 310-foot-tall Parson Jones Tree and the 1,400-year-old Colonel Armstrong Tree. I found it humbling to walk along the mossy trail through some of the oldest, tallest trees on the planet.

After hiking among these ancient giants, I went to Healdsburg, where tasting rooms, boutiques, bed-and-breakfast establishments and great restaurants like Chalkboard and Willi’s Seafood & Raw Bar make nice stopping points.

The next morning as I continued toward San Francisco, my final destination, I made my way to Point Reyes National Seashore for a different type of park filled with grasslands, rocky beaches and rugged cliffs. Stop at the Cypress Tree Tunnel, which is an often-photographed road covered by Monterey cypress trees. It’s not on the park map but sits between the lighthouse and the visitor center.

Continuing south along the seashore, I hit the Golden Gate Recreation Area and the Muir Woods National Monument, a primeval forest with trails through coastal redwoods. By the time I drove across the Golden Gate Bridge into San Francisco, I felt a strong connection to nature. The trees and landscapes were incredible, and made me not only appreciate the beauty of the West Coast, but also the work the U.S. park and forest services are doing to keep these areas intact for many years to come.

The Lighthouse at Point Reyes National Seashore

Related

Read more stories about the West Coast.

- Road Trip from Olympic National Park to San Francisco

- DELETE - Road Trip to 5 Indie Bookstores Worth the Drive

- The Bee Journey

- Glamping in Oregon

- Road Trip Along the Oregon Coast

- The Blind Hike

- Road Trip Through Central Oregon

- Oregon Trips

- Mount Rainier National Park

- Washington’s North Cascades National Park

- Pacific Coast Highway - Washington and Oregon

- Washington's San Juan Islands

- Weekend Getaway in Seattle

- Cascades Loop Road Trip

- Visiting Washington's Olympic National Park in the Offseason

- Washington Trips

- Road Trip to Napa Valley, California, Winery

- Road Trip to See Whales

- Rediscovering California’s Eastern Sierra

- Beaches Near Disneyland

- Majestic Mountain Loop Family Fun

- Couple’s Weekend Trip to Solvang, California

- Weekend Getaway to the Ghost Town of Bodie, California

- Nostalgic Route 66 Road Trip: Santa Monica to Albuquerque

- Majestic Mountain Loop

- Road Trip to Napa Valley, California

- Weekend Getaway to San Diego, California

- Road Trip to Five National Parks Near Los Angeles

- Weekend Getaway in Joshua Tree National Park

- Road Trip Through Northern California

- California Coast People

- Road Trip to Big Sur

- Surfing on the West Coast

- Weekend Getaway to Half Moon Bay

- Weekend Getaway to Fresno, California

- Road Trip to Calistoga, California

- Weekend Getaway to San Luis Obispo

- Fall Foliage Road Trip in Road Trip From San Francisco to Yosemite

- DELETE - Road Trip to 5 Midsize Cities With Thriving Art Scenes

- Pacific Coast Highway - California

- Road Trip along California's Redwood Coast

- California Trips

- Weekend Getaway to Yosemite National Park

- Insider's Guide to San Francisco Attractions

- Modern-Day Prospectors

- Rescue Relay

- Road Trip to Death Valley National Park

- Road Trip to See California Wildflowers